Thinking In Human

Reclaiming Comprehension in an Age of AI-Generated Code

We’re in the middle of a shift. LLMs write faster than we can review. Context windows stretch into the millions. Agentic tools like Claude Code and Cursor don’t suggest code—they architect entire codebases. We stopped asking for snippets and started asking for features.

In 2026, coding has become a flood. Codebases generated primarily by prompts. PRs larger and harder to read. Working software that once required expert engineers now assembled from components no one on the team fully understands. The tools caught up to production but we haven’t caught up to comprehension.

Context windows keep expanding—and it’s never enough. My side projects these days usually blow past that after a few days of work. So when you ask “how does authentication work here?”—the LLM does what it can. It greps. It pattern-matches strings. It returns hundreds of lines containing “auth” and hopes one of them is what you meant. The model reaches for the same blunt tools we do.

Operator and instrument alike, navigating contexts too large to hold. This is the new constraint—not writing code, but orienting within it. We need a way to search by meaning.

This is what semantic search offers. Not pattern matching—understanding. You ask “how does authentication work?” and it finds verifyToken, SessionValidator, IdentityManager—even though they share no characters with your query. The search operates in concept-space, the same space humans think in.

The idea isn’t new. Vector embeddings, similarity search, retrieval systems—I already use them in my own tooling. But applying them to code navigation, wiring them into the tools developers already use, making them local and fast enough to feel native—that’s the gap.

What follows are five ideas I kept returning to while building—about how we navigate the flood, what it costs to understand unfamiliar code, and what it means to stay in the loop when the loop moves faster than we can follow.

The Flood

The flood doesn’t hit everyone the same way.

Senior engineers feel it in code review. PRs arrive faster, larger, but often disjointed. Developers ship the first code that works rather than stepping back to test assumptions. The code solves the problem but misses the better solution. It satisfies speed but loses in coherence.

Juniors feel it in the false confidence. Every prompt gets affirmed, every idea validated—until code review. The code works in isolation, then a senior leaves twelve comments: Why are there hardcoded API keys? Placeholder error messages instead of code? The same database call pattern in four different files? Even though the model said it looked great at every step.

I’ve been on large client projects where we intake a new POC to prepare for production. The team concludes everything is okay because the model says so. But with some old-school engineering—actually peering into the outputs—you see the issues clearly. I’ve learned not to trust everything that looks good. You need a proper feedback loop.

The institutional memory is a thing of the past. Large codebases are already difficult to navigate when they involve domain knowledge you’re unfamiliar with—CAMELS ratings in banking, healthcare compliance schemas, legacy payment routing logic. When your team isn’t familiar, it gets really hard finding the right folks to verify what you’re looking at. There’s no one to ask “why did you do it this way?” because often times no one did it any way—they described what they wanted and the model obliged.

This is where the old tools break down. Grep finds “auth” and returns 847 lines. Ripgrep is faster but still literal—it doesn’t know that verifyToken, SessionValidator, and IdentityManager are all answers to “how does authentication work?” You need conceptual search, but the files are massive and the LLM chokes. You were supposed to be moving faster. Instead, you’re deep-diving to fill gaps that shouldn’t exist.

When I built semantic-code, it was because of that experience. Even though I could grep the entire filesystem, sometimes I just needed to know conceptually what the pieces were and how they fit together. Not just pattern matching—understanding. But to make that work, the search needs to understand code structure, not just lines of text.

You’ve likely experienced this too. Maybe you were debugging a complex system and needed to find where authentication was implemented, but grep just returned hundreds of lines of code with “auth” in them. Or you were trying to understand how a new teammate’s code worked and couldn’t find the right functions.

This is what makes semantic search so valuable—it’s not just faster, it’s smarter about understanding what you’re really looking for.

The Cognitive Tax

Every developer carries a mental dictionary. Concepts map to code. “Authentication” in your head becomes verifyToken in this codebase, AuthService in that one, IdentityManager somewhere else. On a familiar project, the translation is automatic. You’ve built the mapping through repetition—weeks of PRs, code reviews, debugging sessions. The dictionary is cached.

On an unfamiliar codebase, you translate manually. You grep for “payment” and get nothing. You try “transaction”, “billing”, “checkout”. Eventually you findRevenueOrchestrator. Each failed search is cognitive load. Each guess is a tax you pay to build the dictionary from scratch.

Maybe you’re working on a codebase with a completely different naming convention than what you’re used to, and you’re constantly guessing what functions do what. Or you’re trying to understand a domain-specific codebase where the terminology is foreign.

In the pre-AI era, this tax was annoying but manageable. You worked on one, maybe two codebases at a time. You had weeks to build the mental model. The team used consistent naming because a human wrote it with continuity in mind. The dictionary, once built, stayed stable.

The AI era changed the cadence. Context-switching accelerated. You’re a consultant reviewing three client codebases in a week. You’re a team lead jumping between five services, each generated by different prompts, different developers, different models. You’re an engineer inheriting a POC that was built in two days by someone who’s already moved on. The dictionary resets constantly, but the expectation is that you move faster.

The flood compounds the tax. AI-generated code works but lacks naming coherence. One file calls it handleUserAuth, another calls it validateIdentity, a third just says checkAccess. They’re conceptually identical, textually unrelated. Grep can’t help you. The LLM can’t help you—it’s doing the same string matching, returning the same 847 lines, hoping one of them is what you meant.

You’re a human manager trying to understand the flood of code that an AI produces, but your tools only speak in literals. You think in concepts, the codebase speaks in arbitrary tokens, and there’s no translation layer. The cognitive tax becomes the bottleneck—not writing code, but orienting within it.

What if the search operated in concept-space instead?

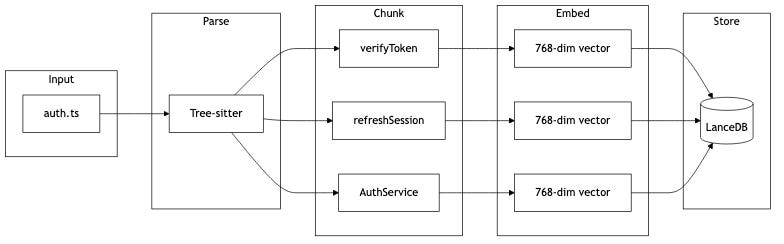

This is what vector embeddings do. Code becomes high-dimensional vectors—768 numbers capturing semantic meaning. Functions that do similar things cluster together in vector space, regardless of what they’re named. When you search “authentication”, the embedding model places your query near verifyToken, AuthService, and IdentityManager because they share conceptual proximity, not characters.

The translation layer disappears. You stay in concept-space—the space humans think in—and the tool handles the mapping. The cognitive tax drops. The ergonomics finally match the problem: a human manager navigating AI-generated code at AI-generated speed.

Orchestration Over Delegation

There’s a fork in how we use AI tools. One path: hand everything over. “Claude, fix this bug.” “Claude, refactor this module.” “Claude, add error handling.” The other path: stay in the loop. “Where is the bug?” “What does this module do?” “How is error handling implemented?”

The first path is faster in the moment. The reflex is strong—why spend twenty minutes tracking down a function when the AI can do it in thirty seconds? But the reflex has a cost. Muscles weaken when you don’t use them.

This isn’t about pride. It’s about what happens when you delegate understanding. When you ask “do X for me,” the AI does X. When you ask “where is X,” you learn the codebase. The first path gets you an answer. The second path builds a mental model.

The flood makes this distinction critical. On a familiar codebase, you can delegate safely—you know enough to review what comes back. On an unfamiliar codebase generated by AI, delegating compounds the problem. You’re outsourcing comprehension of code that already has no institutional memory. The gap widens.

The alternative is orchestration, not delegation. You ask questions. The tool surfaces possibilities. You interpret, decide, and act. You stay in the loop—not because you distrust the AI, but because the loop itself is where learning happens.

This is a different kind of relationship with AI. Instead of asking “fix this,” you’re asking “help me understand this.” Instead of giving up control, you’re staying engaged.

This is why semantic-code uses hybrid search. Vector search finds conceptual matches—functions that handle authentication, even if they’re named differently. BM25 keyword search finds exact terms—when you know you’re looking for verifyJWT, it ranks that at the top. A cross-encoder reranker refines both, boosting the most relevant results.

The system gives you both: the flexibility to search by meaning when you’re exploring, and the precision to find exact matches when you know what you’re looking for. But crucially, you’re the one interpreting the results. The tool surfaces options. You decide what matters. You stay in the loop.

The atrophy risk is real. The more we delegate, the less we understand. The less we understand, the more we have to delegate. Orchestration breaks the cycle. The tool amplifies your ability to navigate the flood, but you remain the navigator.

Tools as Arguments

Building a tool is making an argument. Every design choice is a claim tested against reality. The code either works or it doesn’t. The performance is either acceptable or it isn’t. The ergonomics either fit the workflow or they get in the way. You can’t hide behind rhetoric when the tool fails.

This is what makes tools honest. When I say “semantic search should understand code structure,” that’s not just a claim—it’s a bet. If AST-aware chunking doesn’t improve search quality over line-based splitting, the tool fails and the argument falls apart. The artifact is the evidence.

The structure follows the pattern of argument: Claim → Warrant → Evidence → Concession → Implication.

The claim: Search should operate in concept-space, not just pattern-matching strings.

The warrant: The cognitive tax is real. The flood is here. Grep returns 847 lines and doesn’t know that verifyToken, SessionValidator, and IdentityManager are all answers to “how does authentication work?” The existing tools don’t match how developers think.

The evidence: Each component is a claim tested in code.

- Tree-sitter parsing respects code boundaries—functions stay whole, not split mid-logic. Tree-sitter is a syntax parser that understands code structure at a deeper level than simple line parsing. It reads the actual structure of code, not just lines of text.

- Local embeddings (nomic-embed-code, 768 dimensions) run on your machine—no API calls, no data leaving your system. These are machine learning models that convert code into mathematical representations that capture meaning.

- Hybrid search combines vector similarity with BM25 keyword matching—you get conceptual search and exact-term precision. BM25 is a traditional information retrieval technique that ranks results by keyword frequency. It’s like a smart search engine that knows what you’re looking for.

- Cross-encoder reranking refines results—higher accuracy than vector search alone. This technique re-ranks initial results to improve precision. It’s like having a second opinion that makes sure the results are truly the best matches.

- MCP (Model Context Protocol) wires it into tools you already use—Claude Code, Cursor, any AI coding assistant that speaks MCP. MCP is a protocol that allows AI tools to access local context and tools. It’s like connecting your AI assistant to your local development environment.

Each piece could have been different. I could have used OpenAI embeddings (more accurate, but requires API calls and costs money). I could have skipped reranking (faster, but lower precision). I could have built a CLI instead of an MCP server (easier, but doesn’t integrate with existing workflows). Each choice is a bet on what matters most.

This is the power of building with intention. Every decision reflects what you value most in your development workflow.

The concession: What I traded away to make those bets.

- Slow first index. Parsing and embedding a large codebase takes time—minutes on a big repo. Grep is instant. I traded startup speed for ongoing search quality.

- 400MB model download. The embedding and reranking models live locally, but they’re not small. You download once, but it’s still a barrier.

- Won’t beat grep at literals. If you know the exact function name, grep is faster. Semantic search shines when you don’t know what you’re looking for—when you’re navigating by concept, not by string.

The concessions are what make the argument honest. Most tools hide the tradeoffs. When you name what you gave up, readers know you’re not pitching—you’re thinking through the problem.

The implication: If the components hold up—if AST chunking improves quality, if local embeddings are fast enough, if hybrid search delivers better results than grep or vector search alone—then the tool proves the claim. Search can operate in concept-space. The cognitive tax can drop. Developers can navigate the flood without drowning.

The tool is the argument. The code is the evidence. The tradeoffs are the honesty.

The Learning Loop

The tool is residue. The loop is the point.

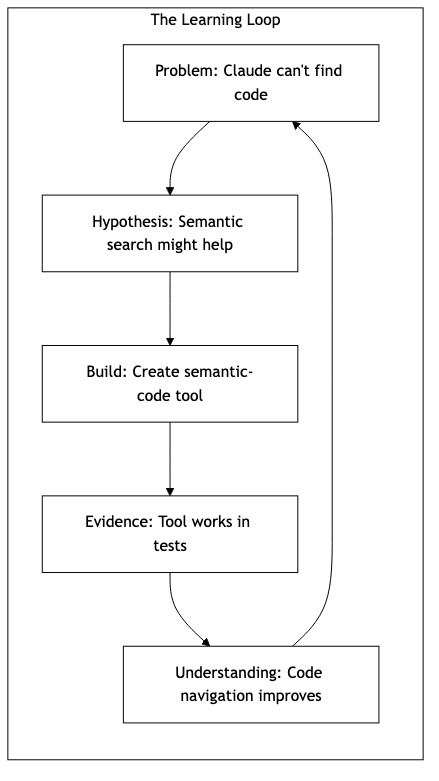

I didn’t start with “I’ll build an MCP server for semantic code search.” I started with “Claude can’t find the right code in unfamiliar repos.” The problem came first. The hypothesis followed: maybe semantic search could close the gap. The build tested the hypothesis.

It could have failed. The embeddings could have been too slow. The chunking could have produced worse results than line-based splitting. The MCP integration could have been too clunky to use in practice. If any of those had been true, I would have learned something different—but I still would have learned.

This is the loop: Problem → Hypothesis → Build → Evidence → Understanding.

The artifact—the working tool—proves I went through the loop. But the loop itself is the point. The enemy isn’t ignorance. The enemy is accepting answers instead of building understanding.

In the AI era, it’s easy to stop looping. You ask Claude for an explanation, it gives you one, and you move on. You ask for code, it writes it, and you ship it. The answers arrive faster than you can verify them. The reflex is to trust and proceed.

But answers aren’t understanding. Understanding comes from testing hypotheses against reality. From building something and watching where it breaks. From making bets and learning what you traded away.

The first time I searched “authentication” in semantic-code and it returned IdentityManager from a file I’d never opened—and it was exactly right—I felt something. Not just relief. Recognition. The tool was doing what I do when I understand a codebase: mapping concepts to code, clustering related functionality, ignoring surface-level naming differences. It wasn’t magic. It was the loop made visible.

But here’s what’s important—this loop isn’t just about my experience. You’ve probably had the same moments. When you’re trying to understand a new codebase, and suddenly the right piece of code appears, you know exactly what I mean. That’s the value of staying in the loop.

This isn’t just about tools—it’s about maintaining human agency in development. The learning loop is what keeps us engaged, curious, and growing. When we’re in the loop, we’re not just consumers of code—we’re creators and architects of our understanding.

This is what the diagram shows: you ask a question, the AI uses the tool, the tool searches, the results come back. But the real loop is invisible in the diagram. It’s the one where you interpret the results, ask a follow-up question, read the code, form a hypothesis about how it works, and test that hypothesis by searching again. That’s where the learning happens.

The tool makes the loop faster. It doesn’t replace the loop.

The risk in 2026 isn’t that AI will replace developers. It’s that developers will stop looping—stop testing hypotheses, stop building understanding, stop questioning the answers they receive. The flood will keep coming. The tools will keep generating. And we’ll have working code that no one understands.

The learning loop is the defense. Problem → Hypothesis → Build → Evidence → Understanding. It doesn’t matter whether you’re building an MCP server or just trying to understand someone else’s codebase. The loop is the same. Stay in it—and remember, you’re not alone in this journey.

What can you start doing today? Try asking “where is this function?” instead of “fix this bug.” Try exploring the codebase with semantic search before diving into implementation. The act of asking questions and seeking understanding is what will keep you sharp in this rapidly changing landscape.

Final Thoughts

This isn’t about replacing human thinking with AI. It’s about keeping human thinking alive in an age where the tools can outpace understanding. We’re not trying to make code easier to write—we’re trying to make it easier to understand.

The future of development isn’t about having more powerful tools. It’s about having better relationships with the tools we already have. The goal isn’t to stop learning— it’s to make the learning process more efficient, more intuitive, and more human.

When you stop asking “what should I build?” and start asking “how can I understand what I’ve built?” you’re on the right path. The tools are just helpers— the thinking is what matters.

The flood isn’t going away. But the way we navigate it? That’s something we can shape together.

What’s your experience with the AI flood? Have you found yourself spending more time understanding code than writing it? What tools have helped you maintain that human connection to your code? I’d love to hear your thoughts on how we can all stay in the learning loop together.

Take Action

Here are three ways you can start applying these principles today:

1. Try semantic search in your current projects - If you have access to semantic search tools, use them to explore codebases before diving in

2. Question your delegation patterns - When you ask an AI to fix something, also ask “where is this code?” to maintain your understanding

3. Document your learning loops - Keep notes about when you discover concepts in code that you didn’t expect, and how that changed your understanding

The key is to build a relationship with your tools that enhances, rather than replaces, your thinking.